The Schneider Story

Written by Mark Blois-Brooke

In the early part of the 20th century Jacques Schneider, a wealthy French industrialist and aircraft enthusiast with a taste for adventure, was convinced that the future of aircraft lay in seaplanes as so much of the Earth is covered in water. In 1912, at the Aeroclub de France, he proposed to the assembled members an annual contest for seaplanes to support the progress of aviation in general - and seaplanes in particular.

The idea of the contest was accepted and so was born the famous Schneider Trophy. Whichever pilot, or nation, that could win three consecutive races in five years could keep the trophy and the winning pilot win 75,000 Francs for each of the wins.

The Schneider Trophy

The word spread quickly and the first race was held off the beach in Monaco on 16th April 1913 over a six lap 300 km course. It was won by a French pilot, Maurice Prevost in a Deperdussin Monocoque powered by a 160-hp, 14-cylinder Gnôme rotary engine at an average speed of 45.7 mph. The Trophy was proudly displayed in the offices of the Aeroclub de France for the first - and last time.

The contest became not one of improvements in reliable long-range seaplanes, as M. Schneider originally wanted, but rather one of intense competition between nations with one aim in mind – to build the fastest seaplane in the world and become the dominant nation in aircraft development.

Following the inaugural race in 1913 the Trophy was contended again the following year, again in Monaco. Three nations entered aircraft, Great Britain, France and Switzerland. The Great Britain entry was prepared by T.O.M. Sopwith, founder of the famous Sopwith Aviation Company who selected the Sopwith ‘Tabloid’ as the race contender. The ‘Tabloid’ was originally a land plane that was modified to floats specifically for the race. Although the aircraft used wing warping for control and side-by-side seating the design was advanced for its time with the engine enclosed by an aluminium cowling, cooling air being admitted through two small slots at the front. The engine was a 100hp Gnome Monosoupape (‘single valve’), a French rotary engine that Sopwith collected in person from Paris to ensure safe delivery.

The Soptwith Tabloid & Howard Pixton

The ‘Tabloid’ set the standard for a series of famous Sopwith aircraft including the Sopwith 1 ½ Strutter, the Pup, the Triplane and the legendary Camel. For the first time the development of Schneider Trophy aircraft led directly to fighter development, a common theme of the event.

Following the inaugural race in 1913 the Trophy was contended again the following year, again in Monaco. Three nations entered aircraft, Great Britain, France and Switzerland. The Great Britain entry was prepared by T.O.M. Sopwith, founder of the famous Sopwith Aviation Company who selected the Sopwith ‘Tabloid’ as the race contender. The ‘Tabloid’ was originally a land plane that was modified to floats specifically for the race. Although the aircraft used wing warping for control and side-by-side seating the design was advanced for its time with the engine enclosed by an aluminium cowling, cooling air being admitted through two small slots at the front. The engine was a 100hp Gnome Monosoupape (‘single valve’), a French rotary engine that Sopwith collected in person from Paris to ensure safe delivery.

The ‘Tabloid’ set the standard for a series of famous Sopwith aircraft including the Sopwith 1 ½ Strutter, the Pup, the Triplane and the legendary Camel. For the first time the development of Schneider Trophy aircraft led directly to fighter development, a common theme of the event.

After a satisfactory test flight on April 7th of that year, the aircraft was shipped to Monaco for the race. Flown by Sopwith’s test pilot Howard Pixton, the ‘Tabloid’ won comfortably and the Trophy was duly moved to the Royal Aero Club in London. The variant of the winning ‘Tabloid’ was renamed the Sopwith ‘Schneider’. It’s average speed around the course was an exhilarating 86.82 mph, nearly double the speed of the previous year.

The race for ultimate speed was definitely on!

The Great War from 1914-18 meant that the 1914 race was the last to be held for five years. In 1919, the racing restarted with Great Britain the host country following its win in 1914. However, having just come out of a world war, nations were war weary and only three entered the race; Great Britain, Italy and France. The race, held off Bournemouth on September 10th, was not a great success due to the foggy conditions which was both hazardous for the contestants and disappointing for the spectators.

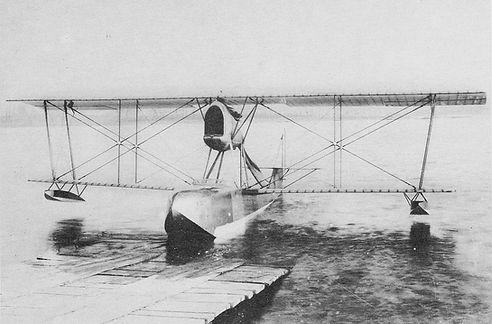

The 1919 SIAI S.13

Great Britain’s entries were a Supermarine ‘Sea Lion’, a Fairey III and a Sopwith ‘Schneider’ – the development of the Sopwith ‘Tabloid’ that won in 1914. Both the Sopwith and the Fairey entries abandoned the race due to the dense fog, while the Supermarine aircraft hit debris and sank while alighting to try and find where it was on the course. The French entries were a Spad and a Nieuport but the only aircraft to actually complete the race was an Italian SIAI S.13.

Unfortunately, the pilot Guido Gianello, was disqualified because, in the poor visibility, he consistently missed one of the turning points, mistaking a boat anchored in a cove southwest of the starting point for one of the three official marking boats. The race was voided and the Italian delegation was outraged - only partially mollified when the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, which controlled the race, invited the Royal Aero Club of Italy to manage the next year’s race.

All eyes turned to Venice for the 1920 race!

The next two years belonged to the Italians however it was noticeable that the huge crowds that had gathered in previous years were absent. The grim post - war economic climate had dampened public excitement in the event and money was tight. It was well known that at this time the Italians made the most advanced flying boats available and no individual or nation turned up to challenge them in 1920.

The Macchi M.7

So, in some ways, the race in Venice in 1920 was a non-event. The race was held between the 19th and 21st of September that year. Pilot Luigi Bologna completing the 230.68-mile course in a Savoia S.12bis powered by a 500-hp Ansaldo V-12 engine, flying at an average speed of 105.97 mph. Venice was again the setting for the race the next year on August 6th and 7th 1921 — and again the race was dominated by the Italians with the only competitor from France withdrew when its floats were damaged. The race winner, Giovanni de Briganti, flew a Macchi M.7bis flying boat with a 280-hp Isotta-Fraschini V-6A engine through the 244.9-mile course at an average speed of 117.85 mph.

The Italians seemed unassailable and only had to win on one more occasion to keep the Trophy for good according to the rules of the race. However, in 1922 their fortunes changed when Great Britain re-entered the fray with an aircraft designed by the brilliant R.J. Mitchell.

After two consecutive wins by the Italiansin 1920 and 1921 the pressure was on to produce a machine that could take them on and win. The brilliant aeronautical engineer R.J. Mitchell, chief designer at Supermarine, came up with the first of his Schneider Trophy winning aircraft - the Supermarine Sea Lion II. Great Britain was back in the game! The 1922 race, hosted by the Italians as winners of the two previous wins, was held in Naples bay in warm and sunny conditions between August 10th and 12th. Three countries entered the field, Great Britain, France and Italy. The French entrant failed to enter on the day, so the race became a duel between two nations, Great Britain in the ‘Sea Lion’ and Italy in two aircraft the Macchi M.17 and the Savoia S.51.

The Supermarine Sea Lion II

The Sea Lion II, G-EBAH, powered by a 450hp Napier Lion II engine was a ‘pusher’ configuration as was customary amongst seaplane designers of the day. Skilfully flown by Henry C. Biard, the aircraft completed the course at an average speed of 145.72 mph narrowly beating the Italians and winning the race. As the race victors, Great Britain was entitled to host the race the following year. However, its victory was to be short lived as another country entered the race – the United States.

From now on, speeds and aircraft sophistication were to increase considerably!

Having won the 1922 race in Naples, it was Great Britain’s turn to host the event in 1923, this time at Cowes on 27th- 28th of September. The triangular course (including Selsey Bill – Southsea – Cowes) totalled only 186nm over the five laps, the shortest total distance to date. The entrants for this year’s race were the USA, Great Britain and France; Italy’s entrant unfortunately failed to materialise.

As part of a public relations exercise both the US Navy and Army were financing racing aircraft and their eyes naturally turned to the Schneider Trophy. In 1923 the US Navy entered a Curtis CR-3 powered by a 465 hp Curtis D-12 liquid-cooled engine. Piloted by Lt. David Rittenhouse, this aircraft was converted from a land racer. It easily won the race at an average speed of 177.3 mph.

As evidence that this was no fluke, second place was awarded to another CR-3 flown by Lt. Rutledge at an average speed of 173.4 mph. Great Britain’s Henry Biard came in third at 157.2 mph flying G-EBAH, an extensively modified version of the Supermarine Sea Lion in which he won the previous year’s race but now fitted with a more powerful 525hp Napier Lion engine.

Lt. Rittenhouse with the winning Curtis CR-3 seaplane

The Curtis machine, however, was undoubtedly a game changer; muscular, streamlined and reliable. As the Trophy crossed the Atlantic to New York and amid disquiet that the Race was becoming State organised, Europe wondered if it would ever return!

Following the convincing performance of the US Navy in 1923 at Cowes ,where the Curtis CR3s took first and second place, progress in Europe was disappointing. Italy and France both announced their withdrawal from the contest. Germany’s design, a monoplane from Dornier, designated the S.4, never left the drawing board. In Great Britain, Gloster Aircraft had an order for two small 20ft wingspan Gloster II float biplanes from the Air Ministry and Supermarine was working on their shaft-drive ‘Sea Urchin’ model. Both projects ended in failure; only five weeks before the race one of the Gloster broke a strut in development, porpoised on landing, capsized in a wall of spray and sank. Fortunately, the pilot, Hubert Broad survived. The second Gloster aircraft was still incomplete and so unable to complete its development. The Supermarine Sea Urchin project was finally abandoned, the complex drive configuration proving too complex. With all these setbacks, Great Britain also had to withdraw from the competition.

The Gloster II aircraft with strut radiator covers in place

With no foreign competition and in a magnificent gesture of sportsmanship the United States National Aeronautical Association wrote to the Royal Aero Club in London suggesting a postponement of the race to the following year – even though all they had to do was fly the course to claim the trophy for ever. This magnanimity prolonged the life of an extraordinary competition enough to indirectly influence events in the coming world war as aircraft development continued apace. All eyes now turned to the 1925 race in Baltimore!

In 1925, monoplanes appeared in the form of R.J Mitchell’s beautiful Supermarine’s S.4 and the Macchi M.33. Biplanes had not disappeared altogether though with the US still fielding the Curtis R3C-2 and Great Britain the Gloster III.

The Supermarine S.4 was built in only five months. It first flew on 25th August 1925 at Calshot but suffered from some handling issues including wing flutter. However, a few weeks later Henry Biard achieved an average speed of 226.75mph – a world floatplane record and British air speed record. Things were looking good for the race in Baltimore!

The Supermarine S.4

Unfortunately, however, when the GB contingent arrived in Chesapeake Bay on 6th October things went badly. The weather was terrible, there were no hangars available or even accommodation for the crews. A leaky canvas tent was erected but this collapsed in a gale and damaged the tail of the S.4. Worse, Henry Biard fell ill with influenza and was nursing a broken wrist. However, all the pilots managed to fly their aircraft but three days before the contest, while still unwell, Henry Biard stalled in a turn and crashed the S.4. He bobbed to the surface unhurt but had to withdraw. Finally, the weather cleared and on October 26th the famous Lt. Jimmy Doolittle, US Army, won the race with a speed of 232.56 mph. Second place went to Britain’s Hubert Broad in the Gloster III, with an average of 199.17 mph. The Trophy remained in the US for another year!

1926, Hampton Roads, Virginia. The consecutive US victories at Cowes and Baltimore made this year’s Contest crucial - one more win and the Trophy would stay in the US. However, Benito Mussolini saw a huge propaganda opportunity for Italy to win at Hampton Roads and he made available all the money and facilities necessary for Aeronautica Macchi and Fiat. In England, Supermarine and Gloster were working on new high-speed floatplanes but these were far from being completed so there were no GB entries this year. Macchi’s chief designer had seen the winning Curtiss design the previous year and had also examined the damaged Supermarine S.4 monoplane both of which yielded valuable information which were incorporated in their M.39. An estimated 30,000 spectators assembled to watch the race on 13th November in bright but breezy and choppy conditions. The course was seven 31.06 mile laps of three legs. For the first time all the pilots in the contest were from the armed forces of their countries. The US Navy fielded three pilots flying Curtiss aircraft including the Curtiss R3C-3, a development of the 1925 winner.

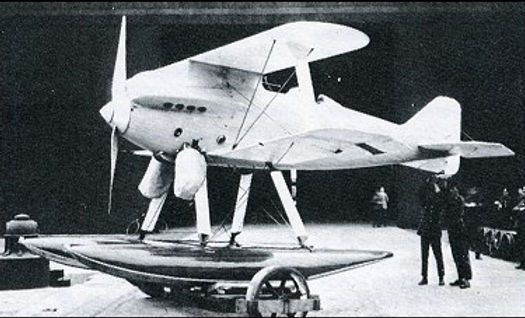

The Macchi M.39

As the race developed it rapidly became a duel between Lt. Cuddihy in the blue and yellow Curtiss and Colonel de Bernardi in the scarlet, 800hp Fiat-engine Macchi. On the last lap Cuddihy suffered from fuel problems and de Bernardi stormed through to win with an average course speed of 246.49 mph. The Italians’ gamble had paid off and the Trophy returned to Europe!

The Untold Story

Following their win in the USA , the 1927 race was held on 26th September in Venice. The

Italians were in buoyant mood, confident of another victory this time on home territory.

They fielded the 1000hp Macchi M.52, an updated, lightened and improved version of the

previous year’s M.39 but engine problems and a fatal accident in practice dampened the

Italian pilots’ panache.

In Great Britain, Supermarine were working on an aircraft to meet the Air Ministry’s

requirements of 265mph and good handling characteristics. Enter R.J Mitchell’s

Supermarine S.5 monoplane. Powered by a powerful Napier Lion engine with innovative

cooling, this was a true 300 mph thoroughbred that first flew in June of that year.

Gloster Aircraft entered the 900hp Gloster IVA/B, that surprisingly retained a biplane

configuration, and Short-Bristow the bullet shaped ‘Crusader’. Altogether, five GB aircraft

shipped to Venice for the race; two S.5, two Gloster IVA/Bs and a sole ‘Crusader’ which due

to its slower speed was used mostly for practice and later crashed.

A Supermarine S.5 in Venice

The American entry lacked government support. A private venture came to nothing and the

US withdrew their participation.

On race day the competition between GB and Italy was fierce. On the 50km triangular

course, the Macchis suffered from engine failures and poor piloting while the British Lion

engines roared powerfully around the course. The Gloster IVB retired on the sixth lap

leaving the two S.5s, flown by Flt. Lts. Webster and Worsley, to complete the course at 281

and 273mph average speeds respectively. British engineering and flying skills had secured

victory!

The Untold Story

In January 1928, it was decided that the Contest should be a biennial event rather than annual and so it was that the next race was in September 1929 in the Solent. At Supermarine, R.J. Mitchell considered that the Napier Lion engine had reached the end of its development.

Rolls-Royce stepped forward with their robust 1500hp ‘R’ engine. This would be mated to the

new all-metal S.6 aircraft, two of which were ordered, the first one flying on 10th August.

Gloster Aircraft meanwhile was working on the beautiful Gloster VI monoplane but the

1320hp engine was troublesome and prone to cutting out in turns. Gloster eventually

withdrew from the Contest.

In Italy, Macchi, Fiat, Savoia Marchetti and Piaggio-Pegna were all tendering designs. In

France, after a six year absence, Bernard and Nieuport-Delage were doing the same. The US

entry, the privately financed Mercury floatplane, turned out to be a non-starter.

The Supermarine S.6 at Calshot, 1929 Contest

Soon however the field thinned out and the final entrants were the new Supermarine S.6 and a S.5 from the 1927 Contest and Macchi with the M.52R and M.67. Weather conditions on

the Solent on 7th September were perfect, sunny with blue skies and a gentle breeze. As the

M.52R and the S.5 engaged in a private battle, Flying Officer H.R. Waghorn in the S.6 tussled

with the M.67, the main Italian threat. It was a race of great drama with burst cooling pipes

and scalded pilots, smoke filled cockpits and misfiring engines as all the machines were

pushed to their limits. Eventually Waghorn prevailed in the S.6 with a phenomenal average

speed around the course of 328.62 mph. One more win and the Trophy was Great Britain’s!

However, involvement in the 1931 race hung on a thread as we will see.

The Untold Story

Incredibly, on the verge of victory, the Royal Air Force decided not to field an entry for the

1931 Contest and instead leave it to private enterprise. Step forward Lady Lucy Houston who

was outraged at this attitude of the Establishment and immediately pledged £100,000 to

ensure GB was represented that year, equivalent to nearly £7m in today’s money. In short

order, Rolls-Royce worked to increase the ‘R’ Series engine to 2300hp and Mitchell worked to

modify the S.6, now the S.6B, to accommodate this extra power and speed.

In Italy, the main threat to GB, Macchi and Fiat were working hard on the MC.72 aircraft

powered by a colossal double-length 50 litre 2850hp engine with contra-rotating propellors.

France struggled to field an entrant and in the end both nations confirmed that neither would compete this year.

The GB Schneider Trophy Team, Calshot 1931

Great Britain now only had to complete the course, that started and finished at Ryde Pier off

the Isle of White, to win and retain the trophy. It was essential to be meticulous in planning

to prevent an embarrassing disqualification. Thousands of spectators watched the

proceedings on the 13th September in ideal conditions. Flt. Lt. Boothman was the first to fly.

In spite of engine cooling problems, he completed the course at an average of 340.08 mph.

After 18 years of fierce competition, the Schneider Trophy was finally Great Britain’s! Not

content with this, in the same afternoon Wng. Cmdr George Stainforth in the S.6B set an

absolute world speed record of 379.05 mph and later in the same month on the 29th and

running of a special fuel cocktail smashed this with another world record of 407.5 mph. He

thus became the first man in history to exceed 400 mph.

There is no question that Great Britain’s success in the Schneider Trophy with the progressive development of the Supermarine S.4, S.5 and S.6 aircraft lead directly to the legendary Supermarine Spitfire. The experience gained in high-speed flight, powerful supercharged engines and sophisticated cooling was invaluable in the Spitfire development which first flew only four and a half years later.

The rest is history.

Sign up!